The Call That Saved Europe the Bog Baby

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/a5/46a59223-d03b-41f4-83e9-8eb3ff8fa432/may2017_e09_bogbodies.jpg)

If yous're looking for the center of nowhere, the Bjaeldskovdal bog is a good place to kickoff. Information technology lies six miles exterior the small boondocks of Silkeborg in the center of Denmark's flat, thin Jutland peninsula. The bog itself is little more than than a spongy carpeting of moss, with a few sorry copse poking out. An ethereal stillness hangs over it. A child would put information technology more than simply: This place is really chilling.

I drove here on a damp March day with Ole Nielsen, director of the Silkeborg Museum. We tramped out to a desolate stretch of bog, trying to go along to the clumps of ocher-colored grass and avert the clingy muck between them. A wooden post was planted to mark the spot where two brothers, Viggo and Emil Hojgaard, along with Viggo's wife, Grethe, all from the nearby village of Tollund, struck the torso of an adult man while they cut peat with their spades on May six, 1950. The expressionless man wore a chugalug and an odd cap fabricated of skin, only nothing else. Oh yes, there was also a plaited leather thong wrapped tightly around his neck. This is the thing that killed him. His peel was tanned a deep chestnut, and his body appeared rubbery and deflated. Otherwise, Tollund Man, as he would be called, looked pretty much like you lot and me, which is amazing considering he lived some 2,300 years ago.

The first fourth dimension I saw him in his glass example at the Silkeborg Museum, a kind of embarrassed hush came over me, as if I had intruded on a sacred mystery. Apparently, this happens often. "Most people get very silent," says Nielsen. "Some people faint, but that'southward rare."

What actually gets you lot is his lovely face up with its closed optics and lightly stubbled chin. It is disconcertingly peaceful for someone who died so violently. You'd swear he's smiling, as if he's been dreaming sweetly for all those centuries. "It'southward similar he could wake up at any moment and say, 'Oh, where was I?'" says Nielsen, who has clearly fallen under Tollund Man'southward spell himself. "Looking at his face up, you feel you could take a trip back two,300 years to meet him. I would like to put a USB plug into his well-preserved brain and download everything that's on it, but that'southward impossible. He's reluctant to respond."

Reluctant perhaps, merely non birthday unwilling. Archaeologists have been asking the aforementioned questions since the Hojgaards beginning troubled Tollund Homo'due south long sleep: Who are you lot? Where did you come from? How did you live? Who murdered yous and why? But the fashion the researchers ask the questions, using new forensic techniques like dual-energy CT scanners and strontium tests, is getting more sophisticated all the time. At that place'south new hope that, sometime soon, he may start to speak.

Scholars tend to agree that Tollund Man's killing was some kind of ritual cede to the gods—perhaps a fertility offering. To the people who put him at that place, a bog was a special place. While most of Northern Europe lay under a thick awning of woods, bogs did not. Half world, one-half h2o and open to the heavens, they were borderlands to the beyond. To these people, will-o'-the-wisps—flickering ghostly lights that recede when approached—weren't the effects of swamp gas caused by rotting vegetation. They were fairies. The thinking goes that Tollund Man's tomb may have been meant to ensure a kind of soggy immortality for the sacrificial object.

"When he was found in 1950," says Nielsen, "they made an X-ray of his trunk and his head, so you tin can meet the brain is quite well-preserved. They autopsied him like you lot would exercise an ordinary body, took out his intestines, said, yup it'south all in that location, and put it dorsum. Today nosotros go near things entirely differently. The questions get on and on."

Lately, Tollund Human has been enjoying a specially hectic afterlife. In 2015, he was sent to the Natural History Museum in Paris to run his feet through a microCT browse commonly used for fossils. Specialists in ancient DNA have tapped Tollund Human's femur to endeavor to get a sample of the genetic material. They failed, but they're not giving upward. Adjacent time they'll use the petrous bone at the base of operations of the skull, which is far denser than the femur and thus a more promising source of Deoxyribonucleic acid.

Then there'southward Tollund Human being'southward hair, which may finish upwards being the most garrulous role of him. Before long earlier I arrived, Tollund Homo'due south lid was removed for the first fourth dimension to obtain pilus samples. By analyzing how minute quantities of strontium differ along a single strand, a researcher in Copenhagen hopes to assemble a road map of all the places Tollund Man traveled in his lifetime. "It'south so amazing, you can hardly believe it'south true," says Nielsen.

Tollund Man is the all-time-looking and best-known member of an aristocracy club of preserved cadavers that have come to exist known as "bog bodies." These are men and women (also some adolescents and a few children) who were laid downwards long ago in the raised peat bogs of Northern Europe—generally Kingdom of denmark, Germany, England, Ireland and the Netherlands. Cashel Man, the community'southward elder statesman, dates to the Bronze Age, around ii,000 B.C., giving him a adept 700 years on Rex Tut. Simply his age makes him an outlier. Radiocarbon dating tells us that the greater number of bog bodies went into the moss some time in the Fe Historic period between roughly 500 B.C. and A.D. 100. The roster from that menses is a bog trunk Who's Who: Tollund Man, Haraldskjaer Woman, Grauballe Man, Windeby Girl, Lindow Human being, Clonycavan Man and Oldcroghan Homo.

They can keep speaking to us from beyond the grave because of the environment's singular chemistry. The best-preserved bodies were all found in raised bogs, which grade in basins where poor drainage leaves the ground waterlogged and slows plant decay. Over thousands of years, layers of sphagnum moss accumulate, eventually forming a dome fed entirely by rainwater. A raised bog contains few minerals and very footling oxygen, but lots of acrid. Add together in low Northern European temperatures, and you have a wonderful refrigerator for conserving dead humans.

A body placed here decomposes extremely slowly. Presently after burying, the acid starts tanning the body'south pare, hair and nails. As the sphagnum moss dies, information technology releases a carbohydrate polymer called sphagnan. It binds nitrogen, halting growth of leaner and further mummifying the corpse. But sphagnan also extracts calcium, leached out of the body's bones. This helps to explicate why, after a k or so years of this treatment, a corpse ends up looking like a squished rubber doll.

Nobody can say for sure whether the people who buried the bodies in the bog knew that the sphagnum moss would keep those bodies intact. It appears highly unlikely—how would they? Still, it is tempting to think so, since information technology fits then perfectly the ritualistic part of bog bodies, perhaps regarded equally emissaries to the afterworld.

Besides, there's likewise the odd business of bog butter. Bodies weren't the only things that ended upward in the bogs of Northern Europe. Along with wooden and bronze vessels, weapons and other objects consecrated to the gods, there was besides an edible waxy substance fabricated out of dairy or meat. Merely this past summertime, a turf-cutter institute a 22-pound hunk of bog butter in Canton Meath, Republic of ireland. Information technology is thought to be 2,000 years old, and while it smells pretty funky, this Atomic number 26 Age comestible would apparently work just fine spread on 21st-century toast. Similar the vessels and weapons, bog butter may have been destined for the gods, but scholars are merely as likely to believe that the people who put it there were simply preserving it for afterward. And if they knew a bog would do this for butter, why non the human trunk too?

Much of what we know about bog bodies amounts to little more than than guesswork and informed conjecture. The Bronze and Fe Age communities from which they come had no written language. There's one matter nosotros do know about them, because information technology is written on their flesh. Nearly all appear to take been killed, many with such savagery that it lends an air of grim purposefulness to their deaths. They've been strangled, hanged, stabbed, sliced and clobbered on the head. Some victims may have been murdered more than once in several different ways. Scholars take come to phone call this overkilling, and information technology understandably provokes no end of speculation. "Why would you stab someone in the throat and then strangle them?" wonders Vincent van Vilsteren, curator of archaeology at Drents Museum in Assen, holland, home of the bog body known as Yde Girl.

We may never get a clear answer, and it at present seems unlikely that a unmarried explanation can ever fit all the victims. But the question keeps gnawing at us and gives bog bodies their clammy grip on the imagination. For some strange reason, we identify. They are so alarmingly normal, these bog folk. You lot call up, there but for the grace of the goddess went I.

That's what overcomes the visitors in Tollund Man's presence. Seamus Heaney felt it, and wrote a haunting and melancholy series of poems inspired by the bog bodies. "Something of his lamentable liberty as he rode the tumbril should come up to me, driving, saying the names Tollund, Grauballe, Nebelgard," Heaney writes in his poem "Tollund Man."

It'south hard to say exactly how many bog bodies at that place are (it depends on whether you count only the fleshy bog bodies or include bog skeletons), but the number is probably in the hundreds. The showtime records of them date to the 17th century, and they've been turning up adequately regularly since then. (Before that, bodies institute in bogs were oftentimes given a quick reburial in the local churchyard.)

We're finding them less frequently at present that peat has profoundly diminished every bit a source of fuel. To the extent that peat withal gets cut at all—environmentalists oppose peat extraction in these fragile ecosystems—the job now falls to big machines that frequently grind up what might accept emerged whole from the slow working of a hand spade.

That doesn't mean the odd bog body doesn't still plough up. Cashel Man was unearthed in 2011 by a milling automobile in Cul na Mona bog in Cashel, Ireland. In 2014, the Rossan bog in Ireland's Canton Meath yielded a leg and arm basic and another leg last yr. "Nosotros know something hugely significant is going on here. We've constitute wooden vessels hither. We've found bog butter. This bog is a very sacred place," says Maeve Sikora, an assistant keeper at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, who is investigating the Rossan finds.

The search for the origins of bog bodies and their secrets goes back a fairly long fashion, too. In 1780, a peat-cutter establish a skeleton and a plait of hair in a bog on Drumkeragh Mountain. The holding belonged to the Earl of Moira, and it was his wife, Elizabeth Rawdon, Countess of Moira, who pursued what we believe to exist the first serious investigation of such a find, publishing her results in the periodicalArchaeologia.

Equally more bog bodies turned up, more questions got asked. In the absenteeism of clear answers, mythmaking and fancy rushed in to fill up the void. On Oct 20, 1835, workmen excavation a ditch in the Haraldskjaer Fen on Kingdom of denmark'due south Jutland peninsula came across the well-preserved body of a woman, about five-foot-two with high cheekbones and long, nighttime pilus. She was clamped to the moss with small staves through her elbows and knees.

Danish historian and linguist Niels Matthias Petersen identified her equally Queen Gunhild of Norway, who, legend tells us, died around 970, and was notoriously brutal, clever, wanton and domineering.

Bog Borderlands

(Map Credit: Guilbert Gates)

According to the old stories, the Viking king Harald Bluetooth of Denmark enticed Gunhild over from Kingdom of norway to be his bride. When she arrived, even so, he drowned her and laid her deep in Gunnelsmose (Gunhild'southward Bog). This explanation was not but accustomed when Petersen offset advanced it in 1835, it was celebrated; Queen Gunhild became a reality star. Around 1836, Denmark's King Frederick VI personally presented her with an oak coffin, and she was displayed equally a kind of Viking trophy in the Church of St. Nicholas in Vejle.

Amid the few dissident voices was that of a scrappy pupil, J.J.A. Worsaae, one of the primary founders of prehistoric archaeology. Worsaae believed the folklore-based identification was hooey. He argued persuasively that the woman establish in Haraldskjaer Fen should be grouped with other Iron Age bog bodies. In 1977, carbon dating proved him right: Haraldskjaer Woman—no longer referred to as Queen Gunhild—had lived during the 5th century B.C. Moreover, a second postmortem in the year 2000 establish a thin line effectually her neck that had gone undetected. She had not been drowned but strangled. This changed everything, except perhaps for the victim.

In the absenteeism of hard evidence, the temptation to weave bog bodies into a national narrative proved hard to resist. The most notorious effort to lay claim to the bog bodies came in the mid-1930s, when the Nazis repurposed them to buttress their own Aryan mythology. By this time, two views prevailed. It was largely accepted that the majority of bog bodies dated to the Bronze and Fe Ages, but their murder was ascribed either to ritual sacrifice or criminal penalty. This latter interpretation rested heavily on the writings of the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus, whoseGermania, written in A.D. 98, portrays social customs in the northern parts of the empire.

On the whole, Tacitus idea highly of the local inhabitants. He praised their forthrightness, bravery, simplicity, devotion to their chieftains and restrained sexual habits, which frowned on immoderacy and favored monogamy and allegiance. These were the noble savages the Nazis wanted to appropriate as direct forebears, and Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo and the SS, established an archaeological institute, the Ahnenerbe, to justify that claim "scientifically."

To the researchers at the Ahnenerbe, bog bodies were the remains of degenerates who had betrayed the ancient code. In a cardinal passage, Tacitus writes: "The penalty varies to suit the crime. Traitors and deserters are hanged on trees; the cowardly, the unwarlike and those who disgrace their bodies are drowned in miry swamps under a comprehend of wicker." Professor and SS-Untersturmfuhrer Karl August Eckhardt interpreted this last phrase to mean homosexuals. It was just a hop from here to the Nazis' ferocious persecution of gay people.

"The Ahnenerbe'due south was the dominant theory of bog bodies at the time, and it was dangerous to question it," says Morten Ravn, a Danish curator who has published a historical overview of bog body research. One of the few who dared was a historian of culture named Alfred Dieck, who perhaps felt himself protected past his ain Nazi Party membership. Dieck's research demonstrated that bog bodies came from as well wide an area over as well long a span of time to represent proto-Germanic legal practice. But the man who torpedoed the Aryan theory of bog bodies was prevented from working as an archaeologist subsequently the state of war because of his Nazi past. Ravn says, "He was really quite an unfortunate person."

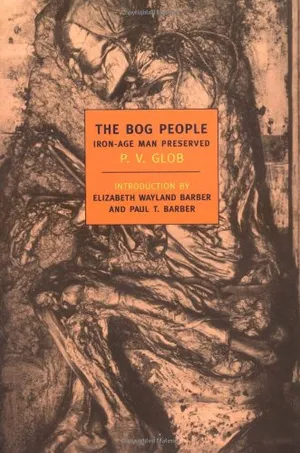

Soon later Tollund Human being was discovered, the detective in charge of what was initially a missing persons investigation had the proficient sense to call in Peter Vilhelm Glob, who had recently been appointed professor of archaeology at the university in Aarhus, the nearest big city. P. Five. Glob, as everyone refers to him, has stamped his proper noun more deeply than anyone else on the riddle of the bog bodies. His book,The Bog People—to the bighearted Glob, they were people, not bodies—was hailed as a modest masterpiece when it appeared in 1965. It is sharp, administrative and moving all at once, and it remains intensely readable. Glob, who died in 1985, succeeded not only in providing the scaffolding for our agreement of Tollund Man and his kin, but in restoring their humanity besides. He conjured bog bodies back to life and fabricated the earth take notice of them. Information technology was Glob who introduced Seamus Heaney to Tollund Human.

In Glob's view, Tollund Man and virtually of the others were sacrificed to Nerthus, the Globe Mother, to ensure a good ingather. We tin see the goddess paraded around, surrounded by fabled animals, on the neat silver Gundestrup cauldron, buried as a sacrifice in a Danish bog non far from where several Fe Historic period bodies were also found. Glob notes pointedly that the cauldron'southward goddesses all wear neck rings and twisted bands on their foreheads—"like the ropes round the necks of sacrificed bog men."

They were strung up at wintertime's end or early spring. We know Tollund Man was hanged, from the mark of the leather loftier upwards on his throat; "if he was strangled, it would take been lower downwardly," Ole Nielsen explains. And nosotros know roughly the fourth dimension of year when this occurred from the seasonal contents found in his stomach and that of other victims: barley, linseed and knotweed, amongst others, but no strawberries, blackberries, apples or hips from summer and autumn.

The ominous conclusion is clear, Glob informs us: The winter gruel was a special last supper intended to hasten the coming of jump, "on just such occasions that bloody human being sacrifices reached a peak in the Iron Historic period."

Glob is fine—much better than fine—as far every bit he goes, but he doesn't get nearly far plenty, as he would no doubt agree. "I'm still trying to get nearer to Tollund Homo," says Ole Nielsen. "In my view, he could take been a willing victim, perhaps chosen from babyhood—I encounter nothing degrading about that. Or maybe they drew straws—'Oh damn! Well, better y'all than me!'

"If nosotros had his DNA, maybe we could say where he came from—his clan, from the northward, from Hellenic republic, wherever. Could he drink milk? Was he prone to diabetes? What almost arteriosclerosis? That'south one of the reasons we sent him for a microCT scan in Paris, to look into his arteries."

Mayhap we shouldn't even exist using the term bog bodies at all anymore, insofar equally it tends to impose a unified explanation on a diverse phenomenon. The offset museum exhibition Julia Farley recalls seeing as a child is the Lindow Human in the British Museum. Lindow Man is the nigh intact of several bodies discovered in the Lindow Moss in Cheshire, England, during the 1980s.

"I still come and say hello to him whenever I'k in the gallery," says Farley, a curator at the British Museum. Except, says Farley, he may non be quite the aforementioned Lindow Man she first encountered all those years agone.

Carbon dating puts his expiry somewhere between 2 B.C. and A.D. 119. We have only the upper half of him, simply besides that he'due south in fine shape. He once stood around 5-foot-six. His beard and mustache had been clipped by shears. His manicured fingernails suggest he didn't work besides hard. His brow is furrowed in consternation. He was just 25 or so when he died, and he died a particularly horrible death. "Ane of the doctors who examined him originally found he had been kneed in the back to bring him to his knees, garroted, had his throat slit, his neck broken, got bashed in the head and was left to drown in the bog," says Farley. "This is the then-called 'triple death,' and it's the model that'south been taken forward."

Farley isn't and then sure, and she's not the simply one. Starting time, the physical show is inconclusive. Farley thinks the sinew tied around Lindow Human being's cervix could as easily be a necklace every bit a garrote. Moreover, some of Lindow Man'due south "wounds" might have occurred after death from the crushing weight of peat moss over centuries. Dissimilar fracturing patterns distinguish basic that fracture before death, when they are more flexible, from bones that fracture after expiry. It matters profoundly, besides, whether Lindow Human lived before or after the Roman conquest of Britain around A.D. 60. Amidst other sweeping cultural changes that came in with the Romans, human being sacrifice was outlawed. What'south more, postal service-Glob, the Tacitus consensus has broken down. Information technology turns out, Tacitus never visited the regions he wrote about, but compiled his history from other contemporary accounts. "At that place's a lot of problematic problems with Tacitus," says Morten Ravn. "He is still a research source, merely you've got to be careful."

All things considered, Lindow Human has gotten roped into a tidy, satisfyingly creepy meta-narrative of ritual killing. "For me, nosotros've got to disentangle Lindow Man from that story," says Farley. "In that location'southward clearly something a flake weird happening in Cheshire in the early Roman period. But we tin't say whether these people are existence executed, whether they've been murdered, whether they've been brought at that place and disposed of, or ritually killed for religious reasons. However it turns out, they're not part of the same picture as the Danish bog bodies. We need to approach Lindow Homo and the other bodies from Lindow Moss every bit individuals—every bit people."

Last October, Lindow Human was taken for a short walk to London'due south Imperial Brompton Hospital, which has a dual-free energy CT scanner. The scanner uses two rotating X-ray machines, each set to different wavelengths.

"Information technology gives yous astonishing clarity for both the thicker parts, such as bones, and the more than fragile parts, such as skin," says Daniel Antoine, the British Museum's curator of physical anthropology. "We're using a dual-energy scanner in conjunction with VGStudio Max, one of the best software packages to transform those 10-ray slices into a visualization. Information technology'south the aforementioned software used in Formula One to browse brake pads afterward a race to reconstruct what'southward happened on the within without having to dismantle it. The software in most hospitals isn't half as powerful as this. We're actually trying to push the science as much as possible."

In September 2012, the museum ran a dual-energy scan on Gebelein Man, an Egyptian mummy from iii,500 B.C. that has been in its collection for more than 100 years. The scan probed hitherto unseen wounds in the back, shoulder blade and rib cage. The harm was consistent with the deep thrust of a blade in the back. Gebelein Human, it appeared, had been murdered. A 5,500-twelvemonth-old offense had been revealed. Says Antoine, "Because the methods are constantly evolving, we can keep re-analyzing the same ancient human being remains and come up up with entirely new insights."

In Republic of ireland, Eamonn Kelly, formerly keeper of Irish Antiquities at the National Museum, claims a distinct narrative for his preserved Irish countrymen. In 2003, peat cutters institute Oldcroghan Man and Clonycavan Man in two unlike bogs. Both had lived between 400 and 175 B.C., and both had been subjected to a spectacular variety of depredations, including having their nipples mutilated. This and other prove led Kelly to propose the theory that the Celtic bog bodies were kings who had failed in their duties. The role of the king was to ensure milk and cereals for the people. (He fills this sacral role past a kingship-union with the goddess, who represents fertility and the land itself.) Kelly's theory was a significant break from bog body orthodoxy. As he explains it, St. Patrick tells us that sucking the male monarch's nipples was a rite of fealty. So lacerated nipples, no crown, either here or in the future.

"In Ireland, the rex is the pivotal member of lodge, then when things go wrong, he pays the price," says Kelly. "All the new bodies discovered since then take reaffirmed this theory. The ritual sacrifice may exist the same principle as in the Teutonic lands, but here you've got a different person conveying the can. To have one caption that fits bog bodies across Europe merely isn't going to work."

Fifty-fifty the Danish bog bodies who furnish the primary narrative are being re-examined to determine how well P. Five. Glob's old story still fits. Peter de Barros Damgaard and Morton Allentoft, two researchers from Copenhagen'south Middle for GeoGenetics, recently examined one of Haraldskjaer Adult female'southward teeth and a piece of the skull's petrous os. They were trying to get a decent sample of her DNA to decide her genetic pool. To get a workable sample would exist a godsend for bog body research, since information technology could clarify whether she was an outsider or a local. To appointment, it has been nearly impossible to get because the acid in bogs causes Deoxyribonucleic acid to disintegrate. But if there'due south whatsoever hope of obtaining some, the sample would likely come from the teeth or petrous os, since their extreme density protects DNA well.

Thus far, the results have proved disappointing. Damgaard did manage to extract a fleck of DNA from Haraldskjaer Adult female'due south molar, but the sample proved besides pocket-sized. "I have no way to certify that the 0.two per centum of human DNA in the sample isn't contaminated," Damgaard wrote to me, after almost a full yr's piece of work. "You could say that the genomic puzzle has been broken into pieces so pocket-sized that they comport no information." He sounded a piffling melancholy about information technology merely resigned. "The DNA of the Haraldskjaer Adult female will be beyond our accomplish forever, so she can lie down and residual."

Karin Margarita Frei, professor of archaeometry/archaeological science at the National Museum of Denmark, had somewhat better luck performing a different kind of analysis on Haraldskjaer Woman'due south pilus. Frei uses strontium isotope analyses in her inquiry. Strontium is present about everywhere in nature, just in proportions that vary from one place to another. People and animals absorb this strontium through eating and drinking in the proportions feature of the place they're in at the fourth dimension—specifically, the ratio of the isotopes strontium 87 to strontium 86. Nosotros accept pretty proficient maps for the strontium characteristics of different countries, so by matching a particular torso's strontium makeup to the map, we tin tell where its possessor has been—and not only at one moment, but over time.

As with DNA, the best places to mine strontium are a person's teeth and basic. The strontium isotope ratio in the first molar enamel shows where y'all come from originally, the long os of the leg volition prove where you spent the last ten years of your life, and a rib will localize you lot for the last iii or four years. The problem is that bog bodies often have no basic and their teeth are terribly degraded.

Frei had a revelation. Why not get together strontium from human hair? "When I saw Haraldskjaer Woman'southward hair in 2012, nearly fifty centimeters long, I realized I had the perfect textile to investigate rapid mobility, since information technology works every bit a kind of fast-growing annal. Information technology was an incredible moment for me," Frei told me. Strontium, she says, enables her to "trace travels in the last years of a person's life."

Hair contains at most a few parts per million of strontium, often much less. And after burial in a bog for a few k years, hair is often fatally contaminated with dust and microparticles.

Information technology took Frei iii years to develop a technique for cleaning pilus and extracting usable strontium samples from it, but when she did, the results were startling. "The small amount of enamel we got from Haraldskjaer Woman'due south teeth said she was raised locally, but the tip of her hair told usa that in the months earlier her death she went quite far. The low strontium signature indicates a volcanic expanse—peradventure the heart of Germany, or the Uk."

Frei did a like analysis on Huldremose Woman, a 2nd-century B.C. bog trunk found in 1879 in a peat bog near Huldremose, Kingdom of denmark. Similar results.

"Both women were traveling just before they died," says Frei. "It made me think that if they were sacrificed, maybe they made the trip every bit part of the cede. We may have to rethink the whole sacrifice question because of strontium."

How fruitful a fashion forrad are these loftier-tech invasions of the flesh? Eamonn Kelly, the Irish bog torso scholar, urges circumspection and humility. "They only don't know enough to say, this is a person from French republic who turned upwardly in Ireland. I do retrieve we're going to go useful scientific advances that we can't even comprehend now, but in that location's also a lot of pseudoscience in the field of archaeology. Scientists give yous a detail effect, but they don't tell you lot most the limitations and the drawbacks."

In this case, information technology might plow out that Ole Nielsen is troubling Tollund Human being's dreamless slumber for very little. One of the reasons for taking off Tollund Human's lid was to send a hair sample to Karin Frei. "Ole has been after me to exercise this for some time, simply Tollund Man's hair is very short," says Frei.

About a year after telling me this, Frei wrote to requite me an early preview of her results. They were meager—much less informative than Frei's investigations of Haraldskjaer Woman. Frei compared the strontium in Tollund Man's short hair with the strontium in his femur. Small differences in the strontium isotope's proportions between the ii samples suggest that while he spent his final year in Kingdom of denmark, he might have moved at least 20 miles in his final six months.

That's critically important for Nielsen. Every new tidbit unravels another thread in the deeply human being mystery of these bog bodies. "It volition never cease. There will ever be new questions," he says. "Tollund Human doesn't care. He'southward dead. This is all about you and me."

Editor's Note: Scientist Karin Frei performed her comparative analysis of the bog trunk Haraldskjaer Woman with Huldremose Woman, not Egtved Girl, as previously stated in the text.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/europe-bog-bodies-reveal-secrets-180962770/

0 Response to "The Call That Saved Europe the Bog Baby"

Post a Comment